One God, or Less.

To be a Jew—even a secular or atheist one— means that if there were a God, it would have to be the Jewish God. Jesus Christ need not apply.

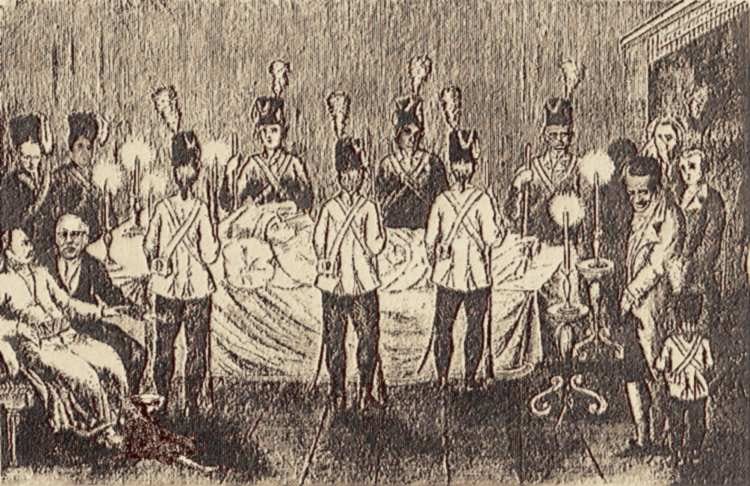

The death of Jacob Frank, 1790

Last week, I was sitting at a café in Tel Aviv with a friend—a survivor of the Nova Music Festival massacre. We were talking about his life in Canada before he moved to Israel when one of his friends, also a Nova survivor, joined us. This friend had just returned from a speaking tour in the U.S., where he shared his traumatic experiences with captivated audiences. One of those audiences, he mentioned, was a “synagogue”—except the congregants there believed that “Jesus Christ was their lord and savior.” This so-called synagogue housed Torah scrolls, displayed mezuzot on its doorposts, and sang in Hebrew, yet its members were devout in their belief that the Messiah had already come and had saved humanity from sin.

“So… they’re Christians,” I said.

He disagreed. “No, they’re Jews, but they follow the teachings of Christ.”

I repeated, “So, they’re Christians, pretending to be Jews.”

Again, he pushed back: “They were born Jewish. They’re Jews. They’re Christian Jews.”

“There’s no such thing,” I replied—and realized we would not agree on how to characterize these people. We let the conversation drop.

This wasn’t the first time I’d clashed with a fellow Jew over whether the “Jews for Jesus” movement—or “Messianic Jews,” as they sometimes call themselves—should disqualify someone from being considered Jewish. I’d had a similar exchange with a Chabad rabbi from my old neighborhood of Crown Heights, Brooklyn. Years ago, he had happily helped me wrap tefillin, even after I told him I was agnostic (though today, I’d define myself as firmly atheist).

I asked him: “Rabbi, would you wrap tefillin on a Jew who declared that Jesus Christ was his lord and savior?”

Here’s how he responded (this conversation has been lightly edited for clarity):

“In Judaism, being Jewish is not based on belief. It's Hotel California (you can check out whenever you like but you can never leave). While there are some actions that may need to be taken in the teshuvah (forgiveness) process, practically speaking, the person is Jewish. The question of someone not being Jewish because they assume some other religion is largely from Reform Judaism, which adopted Judaism as a creed in order for it to better fit into the Christian American understanding of religion... All the more so as many American Jews have defined their Judaism less on its own grounds, and more as what Christianity isn't. Practically speaking: I have put tefillin on such Jews before, and would again. A Jew is a Jew, and without a doubt, a positive action can launch the person on a spiritual journey to better relate to his Jewish identity.”

I then asked the rabbi whether there was any spiritual—or perhaps legalistic—difference between wrapping tefillin on someone born to a Jewish mother who openly declared they didn’t believe in God, versus someone born to a Jewish mother who devoutly followed the New Testament.

His response:

“Nothing to do with tefillin. I care about other Jews.”

I pressed further: “So, is there an equal amount of heresy—or whatever word you’d use—in being a ‘Jewish Christian’ versus being a Jewish atheist? You wouldn’t agree with the idea that, to be Jewish, one must believe in one God or less?”

He replied:

“Why is less less of a problem than more?”

Why indeed.

As it happens, both of these conversations coincided with my reading of Not in the Heavens: The Tradition of Jewish Secular Thought by David Biale, a devoted Jewish secular scholar who passed away last year (may his memory be a blessing). I can say with certainty that this book ranks among my absolute favorite works of non-fiction. It takes readers on a journey from the Middle Ages to modern-day Israel and America, exploring the many Jewish intellectuals who theorized about—and often advocated for—an expression of Jewish identity distinct from the traditional framework of rabbinic Judaism.

There was Maimonides, who pioneered “negative theology” (defining God by what God is not, rather than what God is); Spinoza, perhaps the first true Jewish secularist, who equated God with nature; the Reformers and revolutionaries, like Heinrich Heine and Bernard Lazare, who linked Judaism to secular social justice; the Zionists, who tied Jewishness to secular nationalism—Herzl, Lazarus, Ahad Ha’am, Bialik, and Ben-Gurion among them. And beyond these groups were individuals who transcended both nationalism and spirituality, offering their own unique blends of secular thought.

Each “group” Biale discusses reimagined the traditional Jewish pillars of God, Torah, and Israel, challenging and reshaping their meanings for a changing world.

All this to say: after reading Biale’s book, I have an answer to the rabbi’s question—“Why is believing in less than one God less of an issue than believing in more than one?”

Simply put, Judaism has long contained a loud, strong, and powerful tradition of secularism—one that predates modernity. By secularism, I mean the challenge to traditional theological authority, a current that spans everything from the Reform movement to the militant atheism of early Zionists and Bundists.

These Jews—even if they were excommunicated, reviled, or cast out for heresy in their lifetimes (hello, Spinoza; hello, Herzl)—were ultimately absorbed back into the modern Jewish canon. And not just accepted, but lionized by many as great Jews: leaders, thinkers, Jews of consequence.

In stark contrast, Jews who added a god to the Jewish faith—rather than subtracted one—have largely been swept into the dustbin of history. Consider Sabbatianism in the 17th and 18th centuries, a movement that drew far more support than most Jews today realize. When Sabbatai Zvi declared himself the Messiah, hundreds of thousands of Jews embraced his ideology, which involved a public rejection of Jewish law.

Zvi eventually converted to Islam, but his followers—the Sabbatians—persisted in places like Turkey, continuing to call themselves Jews. The broader Jewish world, however, refused to legitimize them.

A related movement, Frankism (not the subject of a conspiracy for world domination as Candace Owens would have you believe), emerged in the 18th century. Its leader, Jacob Frank, declared himself the incarnation of God and a new Messiah. Like Zvi, he managed to attract a substantial following. But in the end, Frank fully converted to Christianity, renounced all ties to Judaism, and today Frankism—if you’ve even heard of it—is regarded as a strange historical footnote, not a legitimate branch of Jewish thought.

The only real exception to this idea—that to be regarded as Jewish, one must believe in one God or less (a quip I’ve borrowed from my friend and mentor Dr. Einat Wilf)—is the phenomenon of the marranos and conversos.

During the Spanish Inquisition, Jews of the Iberian Peninsula were given a brutal choice: leave the country, convert to Christianity, or die. Those who converted became known as conversos, and marranos—a pejorative term meaning “pig” or “filthy one” in modern Spanish—referred either to conversos or their descendants who outwardly practiced Christianity but were accused of (or actually did) continue practicing Judaism in secret.

The reason conversos and marranos are still regarded within modern Jewish culture as Jews—despite the fact that many did come to believe that Christ was the Messiah—is because of the coercive nature of the Spanish Inquisition. In other words, these Jews and their descendants did not add another god to Jewish theology of their own free will. In many cases, they were forced to, and in many others, they continued to identify as Jews in secret, beyond the reach of Catholic priests, kings, and inquisitors.

By contrast, the “Jews” today who voluntarily accept Jesus as the son of God do so under no violent threat. And for that reason, mainstream Jewish culture is right to regard them with suspicion—and often, with revulsion.

That revulsion is not only warranted toward Jews who add a god to their theology—it is also necessary toward Christians who add specifically Jewish customs to their Christianity. And we should stop pretending otherwise, no matter how “good-intentioned” such gestures may seem.

Take, for example, what happened after the October 7th massacre and the surge of antisemitism in the Diaspora: Catholic actress Patricia Heaton took to social media to launch a campaign called “#MyZuzahYourZuzah,” a project of the Christian group The October 7 Coalition, which encouraged non-Jews to affix a mezuzah to their doors as a sign of solidarity with Jewish neighbors.

Within days of its launch, thousands of requests poured into Heaton and her organization from non-Jews eager to incorporate a mystical piece of Jewish culture into their lives. This, I cannot stress enough, was gross.

Rather than flying an Israeli flag outside their homes or placing a lawn sign that read “Stop Antisemitism,” these Christians—like those who larp as Jews in so-called “synagogues” that host Nova festival survivors—chose instead to steal Jewish culture. They co-opted sacred symbols and rituals for their own use.

Chabad Rabbi Shlomo Litvin, a close friend of mine (despite our frequent public theological disagreements), wrote of the project: “This is not the move. There are far better ways for allies to show their support.”

Emily Hauser, a Jewish consultant based in Chicago, echoed this sentiment: “This is so deeply offensive, this American-Israeli Jew first thought it must be a parody. Don’t. Do. This.”

And yet, some Jews defended the campaign. Eylon Levy, former Israeli government spokesperson turned influencer, tweeted: “I think this is a really beautiful gesture of solidarity, and the Jews dunking on this don’t understand how urgently we need our friends and allies to speak up.”

Sigh. Clearly, this debate isn’t settled. But it should be.

There must be theological boundaries around Judaism—“one God or less”—and those boundaries apply both to Jews who appropriate their own tradition in service of another faith, and to Christians who appropriate Jewish culture in the name of solidarity.

One part of David Biale’s book speaks directly to the core argument of this essay: his discussion of Joseph Hayim Brenner. In the early twentieth century, Brenner was so committed to ushering in a new era of Jewish secularism that he believed the Jewish religion itself had to become irrelevant to Jewish identity—ethnicity alone, he argued, should define Jewishness.

Biale notes that, unlike other Jewish secularists such as Ben-Gurion or Hayim Nahman Bialik, Brenner found nothing worth redeeming in the halakha. “The law itself,” Baile writes in describing Brenner’s beliefs, “may have been created out of good motives, but after all these have passed into history, all that remains is evil.”

Throughout Not in the Heavens, Biale emphasizes that Jewish secularism, at its core, is a dialectic—an evolving relationship with religion that is rooted in tradition but ultimately seeks to transcend it. Brenner, however, broke that dialectic completely. He refused to allow even the biblical stories to serve as national myths or ethical touchstones. As he put it: “We must decisively divorce ourselves from the past in order to live in the present.”

Brenner’s break with the dialectic culminated in 1911, when he anonymously published an article addressing the contemporary wave of Jewish conversions to Christianity in the Russian Empire. He saw no problem with it.

Biale writes: “Christianity became a symbol for whether Jewish culture would be bounded by religion alone. For Brenner, secular Jews had no dog in the fight over who was the Messiah, since they did not believe in messiahs sent by Gods from elsewhere. Thus, for a Jew to affirm that Jesus was a Jew was a paradoxical way of using the religion of the other to assert a secular identity.”

Yet even in Brenner’s time, secular Jews found this approach horrifying.

Ahad Ha’am—the so-called “secular rabbi” of Zionism—responded to the essay: “He who denies the God of Israel, the historical force that gave the nation life and influenced its character throughout thousands of years can be a good person, but he cannot be a national Jew, even if he lives in the land of Israel and speaks Hebrew.”

Ha’am did not believe in the God of the rabbis. He viewed God as a “historical force”—something abstract, maybe unknowable, but impossible to deny. Still, he understood that to be a Jew—even a secular one—meant that if there were a God, he would have to be the Jewish god. Jesus Christ need not apply.

But here’s the kicker: Joseph Hayim Brenner was murdered in Palestine during the Arab riots of 1921. Clearly, regardless of what he believed or didn’t believe, his killers still saw him as a Jew—connected to the myths, the history, and the collective fate of his people—enough to be sacrificed on the altar of anti-Zionism.

Brenner’s death raises an unnecessary question concerning the argument of this piece: if a Jew is killed for being a Jew, does it really matter what they believed—or didn’t?

The central thesis of Biale’s book is this dialectic: Jewish secularism did not seek to abolish Jewish theology, but to grow out of it—into nationalism, socialism, Yiddish revivalism, or social justice. It was never meant to erase Judaism, only to transform it.

And it’s from that thesis, bolstered by the dozens of thinkers Biale examines, that I stand by my own: There is no such thing as a Christian Jew.

Even for those who don’t believe in God, there must be lines drawn around what constitutes Judaism—who is in, and who is out. That line falls squarely at belief in one God or less.

If you yearn for something more, if you’ve added to the faith rather than wrestled with it—by all means, go ahead. But know this: your synagogue is a counterfeit. Your Passover “seder” is a revolting act of appropriation. And the mezuzah on your door has no right to be there.

You have not inherited the faith of your ancestors.

You have forsaken it.

BLAKE!!! You write SO WELL! And you've said EVERYTHING I ever wanted to say! I'm in tears!!!! ממש ממש כל הכבוד!!!

Well thought out and beautifully written!