Where Have All the Socialists Gone?

Jewish socialists in the U.S. have abandoned their ancestors’ revolutionary legacy in favor of assimilation, while Jewish leftists in Israel have forsaken the revolution in favor of accommodation.

Famous iconography of the Jewish Labor Bund, circa 1918.

Bernie Sanders is on a bender. Since the U.S. election, the Senator from Vermont has castigated the Democratic Party every day online and in official statements. His analysis, in many respects, is accurate: the Democrats have distanced themselves from the working class, become overly preoccupied with identity politics, and grown too reliant on corporate and special-interest funding in down-ballot races. Sanders reiterates a familiar message, one he has championed throughout his public life: “The very wealthy are doing phenomenally well, while 60% of us are living paycheck to paycheck. It’s time to get big money out of politics and create an economy that works for all people.”

It’s no surprise that I agree with Sanders on this premise. I support the progressive wing of the Democratic Party and similar left-leaning movements worldwide when they advocate for universal healthcare, universal childcare, a $15 minimum wage, the removal of big money from politics, and the redistribution of wealth to fund public transportation, housing, and education. For this reason, I identify as a democratic socialist—but with significant caveats that seem to escape the leadership of the camp, whether in Paris, Tel Aviv, or New York: I firmly support the State of Israel as a Jewish state and its right to self-defense, and consequently, I support a muscular foreign policy that aims to protect democracies and human rights around the world.

As it happens, this caveat immediately expels me from the ranks of democratic socialism, seen by Bernie and the like’s flagrant scapegoating of Israel, growing more impassioned by the day. Though his bid to limit arms sales to Israel failed in the Senate this week, Sanders has continued to accuse Israel of atrocities against Palestinians, including starvation and ethnic cleansing. Meanwhile, he offers no tangible resolutions or proposals to address the broader Middle Eastern conflict, such as increasing costs on Iran, Hezbollah, or Hamas to reduce hostilities and promote peace.

A few months ago, after famed antisemite Jeremy Corbyn re-clinched his seat in Britain’s Parliament and received heartfelt congratulations from Senator Sanders, I reflected on the deep, almost spiritual sense of betrayal on Instagram:

“Like many American Jews descended from working-class, Yiddish-speaking immigrants, I supported Bernie’s campaign in 2016. His politics elicited Jewish nostalgia from my family and many others…Yet Bernie’s decision (to congratulate Corbyn) is a tragic reminder that the dominant strain of left-wing politics, that views Jewish particularism as an affront to its values, has triumphed. Tenement-home socialism and its massive contribution to America and humanity is destined to remain a distant memory.”

I also pointed out in this post that Sanders had spent time working on a kibbutz near Haifa in his youth—a fact that only sharpens the sting of the trajectory of socialism in the Bernie variety.

The primary difference between the nostalgic socialism of my family and of the many Jewish families who arrived in America from Eastern Europe, and that of the modern-day Jewish left is the presence of authentic Jewish culture. Today’s anti-Zionist Jews may think they are continuing a proud tradition of radical politics in the Jewish community – but they are not. They don’t have Hebrew, they don’t have Yiddish, they don’t have education in the Tanakh or Talmud like even their most atheist ancestors, and they don’t face labor discrimination on account of their Jewishness leading to communal solidarity. They don’t even have holidays – Passover is ceaselessly universalized to reflect everyone’s struggle for liberation, and Hanukkah is basically blue Christmas. The one thing this lot does wield, the only thing that involves them in Jewish politics, is passionate opposition to Zionism. In other words, the people who claim to be building a Judaism separate from Zionism would have almost nothing to show for being Jewish if not for Zionism.

This is the inconspicuous theme of the film Israelism starring Simone Zimmerman, co-founder of IfNotNow (I call it “I Was Lied to at Summer Camp: The Movie.”) With dramatic music punctuating every scene, Israelism introduces its audience to young Jewish people who are continually connecting to their Jewish identity through Israel. We are supposed to find this repulsive. We are meant to see the Hillel chapter leader on screen as a budding Genghis Khan. While it’s worth noting that Israelism never once mentions a single Palestinian political decision over the last seventy-five years, the movie isn’t truly about Palestinians—or Israelis, for that matter. The conflict is given only cursory attention compared to the film's real grievance: that Jews in the diaspora feel a visceral connection to their counterparts in Israel. This connection fosters a sense of particularity within the Jewish community, which, as it has throughout history, inevitably creates discomfort and tension in a world hostile to difference.

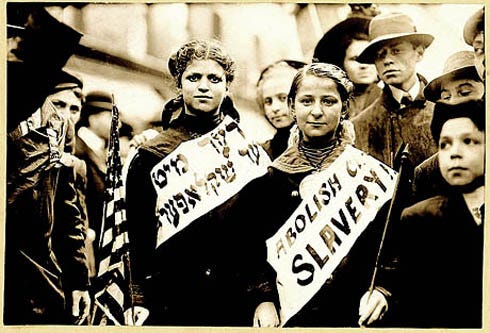

In contrast to the socialism of the politically active yet painfully assimilated, the socialism of the tired and weary yearning to breathe free was aggressively Jewish. The writers, even when contributing to secular subjects (think I.L. Perez), were well-versed in scripture and understood the intellectual value of Jewish theology. The poets knew Yiddish prose. The marches in Washington Square Park for fairer wages featured synagogue congregations and banners in Hebrew. And when Israel declared independence in 1948, this lot overwhelmingly became Zionist, understanding that a Jewish homeland with a democratic-socialist form of government was the closest our people could come to true liberation.

All of this has been lost in the West. Jewish socialists today, like Bernie Sanders, apologize for Jewish liberation. They are extraordinarily uncomfortable with anything too Jewish and have thus purged such elements from their all-too-assimilated lifestyle, whether they would like to believe it or not.

In Israel, regrettably, similar issues persist. The Jewish socialists once grounded in a proud tradition and rich cultural heritage have also lost their way, leaving behind the vibrancy that once defined their movement.

Labor Zionism was the driving force behind the establishment of the Jewish state. Many disagree with this claim, but I stand by it. Yes, there was a spiritual revival in Tzfat centuries before independence was declared. Yes, there was always a Jewish population in the land, and Jews were even the majority in Jerusalem in the decades leading up to the emergence of political Zionism. And yes, there were revisionists with their own ideology and militia, as well as binationalists (who faded into obscurity as violence escalated). But let’s not mince words: it was the Labor Zionists who made the kibbutz. It was the Labor Zionists who built the Haganah. They created an economy and a Histadrut to organize it. They answered Herzl’s call even before it was expressed and were already constructing their vision of utopia while Altneuland was only being drafted.

There is a peculiar tendency in liberal Israeli Jewish spaces to disregard or even denounce this history, as though nothing can be learned from the distinct style of Jewish politics that successfully forged the state. The wounds of past events still linger—the aftermath of the Yom Kippur War, the collapse of the Oslo process, the Second Intifada, and even the trauma of October 7th (though, as I’ve written before, to claim that Hamas’s massacre is somehow an indictment of the left is a grotesque distortion of reality and history.)

The Israeli left has adopted a self-flagellating, subordinate posture. The vision of the "new Jew" that Labor Zionism once championed—strong, confident, and determined—has been replaced by the image of an Ashkenazi Ramat Avivian of a certain vintage, known more for their condescension than any inspiring strength.

A note here: While I frequently critique the Zionist left for its shortcomings, it’s important to acknowledge that, as of the weeks leading up to this writing, Yair Golan—the leader of the Avodah-Meretz merger HaDemokratim—has been polling at around 9–12 seats for the next election. Those numbers are significant and serve as a notable counterpoint to anyone who smugly insists that a Zionist left no longer exists in Israel.

Yet still, 9-12 seats for the Zionist left is a far cry from where it was.

What is happening in Israel offers an intriguing reflection of the dynamics unfolding in America within Jewish progressive politics. In Brooklyn, Jewish socialists advocating for the community’s detachment from Israel are failing to offer anything authentically Jewish in their vision. Their rituals—often performed for the cameras—feel more Christian than anything else (not that I didn’t grow up in a Reform synagogue led by a lesbian, guitar-playing rabbi, but at least we had something to anchor us in Jewish identity beyond mere disdain for the rest of the community.)

Meanwhile, the Jewish left in Israel struggles to articulate a bold, Zionist, transformative vision. Where is the determination to dismantle the Rabbinate’s monopoly over personal affairs? Where is the effective resistance to settlement expansion, the privatization of once publicly owned and trusted media, or the ministers we increasingly recognize as threats to the state? So far, the fight consists mostly of tweets—far from the legislative action that meaningful change requires.

In short, Jewish socialists in the U.S., like Bernie Sanders, have abandoned their ancestors’ revolutionary legacy in favor of assimilation, while Jewish socialists in Israel have forsaken the revolution in favor of accommodation. Where have all the socialists gone? What we see today are Hellenizers in America and a rapidly aging, ineffectual elite in Israel.

Now seems like the right moment to mention that my renewed curiosity about socialism—something I’ve explored before but felt particularly drawn to recently—was sparked by the film Reds (1981), which I first watched in September and have since rewatched eight times. I cannot fully explain this fixation — Warren Beatty is phenomenal, Diane Keaton is luminous, and I have always been obsessed with Eugene O’Neill... pashut, I am a very impressionable young man.)

Speaking of Reds (1981), the only caveat I can think of to this essay at the moment is the Bolsheviks/Bolshevik sympathizers among the Jewish socialists of the early 20th century. Sure, they were there (possibly in my own family), and they did not take kindly to any Jewish particularity, viewing it as a distractive vestige of a less-enlightened time (such is the reason for the title of this publication, Bourgeois Nationalist, a Soviet epithet used against comrades who dared to think of the Jews as a separate and special people, even in private.) This is the Yevsektsia problem: the issue of Jews becoming active persecutors of their own people. The Yevsetskia problem exists everywhere and has since the dawn of Jewish history, taking form currently in explicitly anti-Zionist movements: Jewish Voice for Peace, Neturei Karta, and the radical left in Israel. It is not merely a political problem, it is a problem of Jewish numbers: we are a minuscule minority, and consequently, part of the community is unable to sustain pressure from the wider society. The Yevsetskia problem is never temporary.

What is temporary—if we’re being optimistic—is a mainstream Jewish left in America that mistakenly believes it is continuing the activism of the Jewish left of old and a mainstream Jewish left in Israel that feels ashamed of the Israeli left of old. In America, the dividing line between Jewish socialism today and Jewish socialism of yesterday is the presence of a vibrant Jewish culture. If today’s Diasporic “neo-Bundists” were reviving Yiddish, if they proposed a solution to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict that ensured Jewish survival in the land—rather than doing the bidding of terror organizations that view any Jew as blasphemy—if these neo-Bundists were able to create a space for young American Jews to feel Jewish outside of Zionism, not only encompassing the mere hatred of Zionism, then I would certainly feel more compelled to engage with their arguments and worldview.

In Israel, the dividing line between Jewish socialism today and that of the past is confidence and effective policy. If today’s Israeli left were offering concrete plans to defeat—rather than merely negotiate with—terrorism, if they were willing to disrupt the “business as usual” in the country by forcing the Haredim into the army and cutting off the clergy’s state-provided benefits, if they were firm and uncompromising in their opposition to expanding settlements, I would have far less trepidation and anxiety about the country’s future.

Alas, as I wrote in my Instagram post regarding the betrayal of Bernie Sanders, the fight to salvage the Jewish left will require significant effort and careful strategizing—certainly far more than can be captured in a single Substack entry.